Image courtesy of [Al Jazeera English via Flickr]

Image courtesy of [Al Jazeera English via Flickr]

World

How Does the Hajj Impact the Saudi Economy?

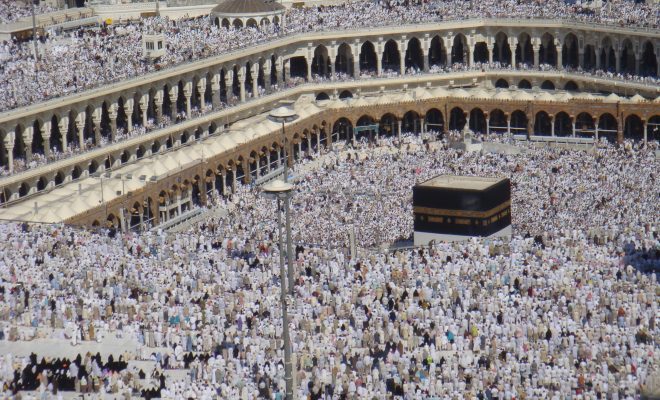

Every year, millions of pilgrims from around the globe trek to Mecca to complete the hajj–the sacred pilgrimage that all Muslims must complete in their lifetime if they are able. The hajj presents massive economic opportunities for the tourism and travel industry. The Saudi economy, which is scrabbling to find other sources of revenue besides oil, has always benefitted from the influx of pilgrims, so much so that revenue from the pilgrims makes up an estimated 3 percent of Saudi Arabia’s GDP.

Pilgrims pay for flights, accommodation, phones, souvenirs, guides, and ground transport, making hajj tourism an incredibly lucrative industry. Families who own property always stand to make money as they can rent out rooms or their entire home to pilgrims for a week. For some, the rent they charge during hajj season can sustain them for months or even until the next hajj. Some travelers sleep at the Grand Mosque rather than paying for a room but most will choose to rest in the “tent city” of Mina where the average pilgrim can find a tent for $500 a night (while a VIP can pay several thousand dollars per night for a luxury tent). Saudi Arabia has actually come under fire for not operating Mina year round as a site for refugees. Using Mina as a refugee camp would lift a great burden off of nations that are currently struggling to support their refugee populations, but it would mean the Saudi government would have to sacrifice part of its hajj profit margin–an act it likely does not feel is worth the risk.

As air travel becomes less expensive, a greater number of people can afford to make the pilgrimage and spend lavishly once they arrive. Saudi retailers who have always counted on the hajj to temporarily boost sales now look to expand the luxury market so that they can maximize sales to the wealthiest pilgrims. Saudi Arabia stands to make as much as $8.5 billion off of the 2016 pilgrimage–but that is a step down from past profits. There are only an estimated 1.86 million pilgrims coming to Mecca this year, as opposed to the almost 3 million who have come in past years. The pilgrims who do come for the hajj are now usually on slimmer budgets–“slim” of course being a relative term considering the average pilgrims will spend over $4,500 on their trip.

This fall, pilgrims from different religions across the world will track routes such as the Camino de Santiago in Europe, the trek to Mount Kailash in Tibet and the Char Dham in India–but none of those routes generate the massive amount of revenue that the hajj does within a matter of days. None of those routes are as fundamental to a national economy nor as closely monitored and regulated as the hajj is in Saudi Arabia. The Saudi economy is now inextricably linked with the hajj–and while there is no sign of the number of pilgrims drying up anytime soon, small drops in attendance can throw off the Saudi economy for a year at a time.

The concept of an entire fiscal year depending on a single week is something we might see in small cities and towns that hold popular festivals (think Telluride or Cannes) but it is rare for an entire country to rely on a cultural event to carry it through the next 11 months. Imagine if the hikers who trekked the Appalachian Trail each September generated 3 percent of the United States’ GDP–our economy would suddenly feel much more precarious depending on the weather, the resource available for those hikers and advertising of the trail to maximize the number of people who hiked it. The drop in the number of pilgrims this year may feel infinitesimal, but if it continues to decline in the future, Saudi Arabia may find itself sitting at the edge of a steep financial precipice.

Comments