Image courtesy of [Ninian Reid via Flickr]

Image courtesy of [Ninian Reid via Flickr]

Entertainment

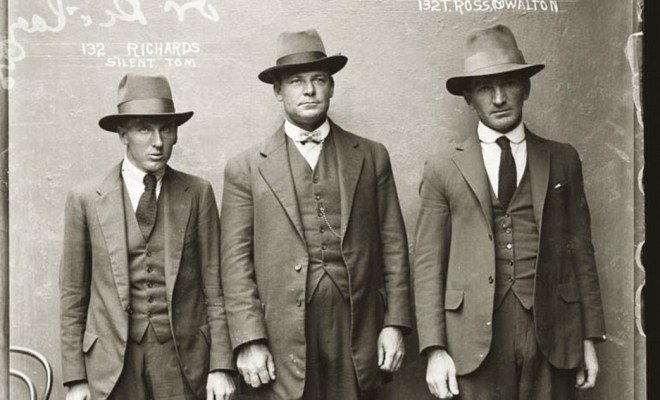

Gangster’s Paradise: The Rise of the Crime Biopic

Who are the heroes of modern American cinema? Marvel’s record-breaking profits and Jurassic World’s massive success this summer were built on ensemble casts performing stylized action sequences with larger than life special effects. The traditional superhero narrative is alive and well in America–underdogs getting bit by spiders, struck by lightning, and using their freakish talents to fight crime. Yet, as integral as superheroes are to popular culture, there has been a parallel movement in film and television that reflects an entirely different underdog narrative: biopics of infamous criminals. These anti-heroes don’t have super strength or mutated genes, they are simply violent and ambitious. Watching them climb the ranks of the organized crime ladder should be disturbing, but instead we find ourselves cheering for the gangsters, projecting our own struggles onto them, and taking their own victories as our own.

According to Thomas Leitch, “the crime film is the most enduringly popular of all Hollywood genres, the only kind of film that has never once been out of fashion since the dawn of the sound era.” Organized crime has inspired directors since the 1930s, when early gangster films presented fictionalized accounts of the rise and fall of Prohibition era criminals. These films did not expressly seek to glorify crime but they represented a shift in American cinema, in which crime became directly connected with wealth and glamour. In the years that followed, American audiences were presented with a host of films that asked the audience to sympathize with the criminal rather than law enforcement.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, directors moved away from fictionalized accounts and began cracking history books to find the heroes of their scripts. A host of real criminals were turned into heroes in modern American cinema–Bonnie and Clyde, John Dillinger, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, to name a few. Writers and directors reached across time periods and geographical borders to assemble epic films that narrate an alternative version of the American dream. Audiences became increasingly disinterested in the fictionalized version of a gangster, loosely interpreted on an amalgamation of different characters. They wanted a true biopic, from birth to death (or incarceration, whichever comes first). “The Godfather” led to “Goodfellas,” “The Departed” led to “Black Mass,” “Boyz in the Hood” led to “Straight Outta Compton”—American moviegoers want a historical account tied to a real individual. This month, the film “Legend” (starring Tom Hardy and Emily Browning) will introduce American audiences to the true story of Ronnie and Reggie Kray, the twin leaders of the Firm, an infamous gang that dominated London in the 1960s. “Legend” is based on the biographical writings of John Pearson, who prior to writing on the Krays, wrote a biography of Ian Fleming. The connection between Pearson’s two biographies should not be overlooked–both examine living, breathing men behind myths.

The gangster film is a consistent moneymaker for Hollywood, promising glamour, action and intrigue for its audience. Yet the rise of the true crime story, the biopic of an individual, represents a pivot away from the escapist nature of crime films. Audiences still want to cheer for the anti-hero, still want to witness the massive robberies and shoot-outs and are still fascinated by men counting stacks of hundred dollar bills from illicit activity, but there is a different note entering this films. Viewers want to know the details behind these figures’ rise to power–their homes, their families, their weaknesses. Half the fun of the biopic is playing armchair psychologist after leaving the theater, puzzling over which events from the protagonist’s childhood made them turn to a life of crime. Hollywood still glorifies organized crime, yet the move away from fictionalized dramas towards well-researched biopics represents a new era of gangster cinema. Viewers are less interested in the destination than the journey–they don’t want to know what criminals do once they reach the top of their game, they just want to know how they got there.

Comments