Image courtesy of [jpellgen via Flickr]

Image courtesy of [jpellgen via Flickr]

News

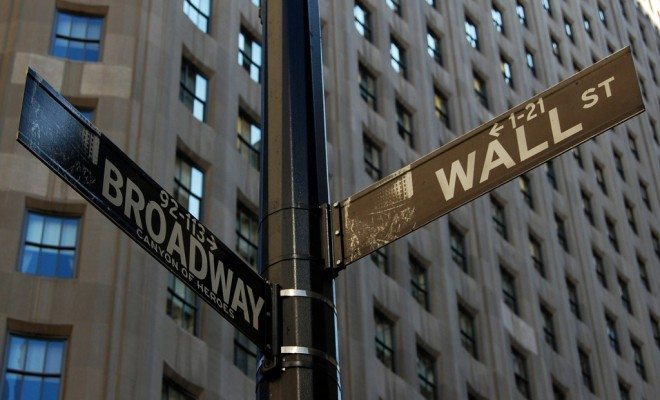

The DOJ is Changing the Way it Prosecutes White Collar Crimes

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Justice Department levied record-breaking fines against many of the big banks involved in the meltdown, but very few individuals actually served time behind bars. That may finally be changing. According to a memo released on Wednesday, the Department of Justice (DOJ) is shifting its priorities to focus on prosecuting specific individuals who are responsible for financial wrongdoing.

“One of the most effective ways to combat corporate misconduct is by seeking accountability from the individuals who perpetrated the wrongdoing,” wrote Deputy Attorny General Sally Q. Yates in a memo to all federal prosecutors. Yates outlined six “key steps” that should guide prosecutors in their handling of corporate misconduct cases. While many of these steps are not necessarily new, the memo seeks to standardize the DOJ’s priorities going forward.

So far, billions of dollars have been collected by the DOJ from fines and civil penalties from major banks for the roles that they played in the financial crisis. However, very few individuals have actually been prosecuted, and even fewer were sentenced to time in prison. This has lead to some harsh criticism of the DOJ and the way that it handles financial crimes.

In an article about the recent DOJ shift, the New York Times notes:

The Justice Department often targets companies themselves and turns its eyes toward individuals only after negotiating a corporate settlement. In many cases, that means the offending employees go unpunished.

While using massive fines allow for record breaking headlines, it also shifts the burden of punishment from the individuals who defrauded the public to a company’s shareholders. Some argue that shareholders should also share in the punishment, as they have a lot of control over a company’s management, but few also argue that the responsible individuals should escape punishment.

The policy shift outlined in Yates’ memo will both prioritize individual prosecution as well as help compel companies to cooperate with investigations, specifically in terms of providing information about responsible individuals. The first point in Yates’ memo instructs prosecutors not to give cooperation credit to a company unless it provides information about all of the people responsible. This cooperation credit can significantly reduce the punishment that companies and individuals receive.

Although the DOJ is not directly admitting that its previous policies were insufficient, Yates does emphasize that her memo marks a significant change. In a speech given at New York University Law School, Yates said:

Now, to the average guy on the street, this might not sound like a big deal. But those of you active in the white-collar area will recognize it as a substantial shift from our prior practice. While we have long emphasized the importance of identifying culpable individuals, until now, companies could cooperate with the government by voluntarily disclosing improper corporate practices, but then stop short of identifying who engaged in the wrongdoing and what exactly they did.

While this memo is certainly notable, it’s actually bringing some white collar prosecution standards in line with established standards for all criminals. In her speech to NYU Law School, Yates also notes that this is how it works for criminals who give information about their co-conspirators to the authorities. She uses the example of a drug trafficker, who can receive a cooperation agreement for informing on other criminals, but will not get any relief if he or she does not give information about the cartel boss. While ending special treatment for corporations is certainly a popular idea, it’s also a little disheartening to hear that hasn’t already been the norm.

This does mark a sort of reprioritization at the DJO, but the question remains: will it matter? Prosecutors face a wide range of challenges when they try to prosecute corporate crime. Yates acknowledges these challenges in her memo, but it is worth noting that this isn’t the first time people have called on regulators to focus on individuals.

The issue isn’t that the penalties for financial crimes are too weak, rather it is simply very difficult to prosecute people in corporate cases. In order to convict someone, prosecutors must trace misconduct to individuals and show intent behind their actions. This can be particularly challenging for issues at the magnitude of the financial crisis, which can involve wrongdoing at several levels of a company, but be difficult to tie executives to. The DOJ can also have a very hard time getting information about what happened; because many banks operate internationally other countries’ laws can restrict the information that is available to U.S. prosecutors.

The recent shift will hopefully make companies more likely to cooperate and provide useful information about individuals, but the prosecutorial challenges remain. Even after the DOJ’s recent announcement, reform advocates remain skeptical. Dennis Kelleher, the head of financial reform watchdog Better Markets told the Huffington Post, “Based on their past dereliction of duty, no one should believe anything DOJ says until they see actual, concrete and repeated prosecution of supervisors and executives.”

Yates is right to say that prosecuting responsible individuals is the best way to discourage future misconduct, but whether that can and will happen remains to be seen. These changes are a step in the right direction and acknowledge the importance of public confidence in regulators, but don’t expect to see many executives in prison any time soon.

Comments