Image courtesy of [Clyde Robinson via Flickr]

Image courtesy of [Clyde Robinson via Flickr]

Law

The Innocence Project: A Shot at Redemption in the U.S. Criminal Justice System

Are you a Netflix user or a fan of the podcast “Serial?” If so, then you’ve definitely heard of the Innocence Project–it’s been a part of Steven Avery’s story in “Making a Murderer,” and the Innocence Project has been investigating Adnan Syed’s case in “Serial” as well. The Innocence Project is a non-profit organization that strives to find the truth when prisoners continually maintain their innocence after they’ve been incarcerated. In the last several decades, it has become all too clear that the American justice system isn’t without its flaws, which sometimes leads to wrongful convictions. It is these wrongful convictions that the Innocence Project strives to fight in hope that they will lead to law revisions in each state. But what exactly is the Innocence Project? Read on to find learn more.

How Did the Innocence Project Get Started?

The Innocence Project was founded in 1992 at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University by Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld as a legal clinic, but later turned into a nationwide project. It was founded after the release of a landmark study by the US Department of Justice and the US Senate that found that 70 percent of wrongful convictions are because of eyewitness misidentification of perpetrators. This study was revised in 1999 to become the manual for law enforcement regarding eyewitness testimony. The Innocence Project became a 501(c)(3) non-profit in 2003 after maintaining its role as a legal clinic at Cardozo for more than a decade.

Both Scheck and Neufeld were law professors at Cardozo and also worked as defense attorneys when they founded the Innocence Project. They are known nationwide as being part of the O.J. Simpson defense team who fought his double homicide charge in 1995. Notably, Simpson was found not guilty in that case in one of the most infamous invocations of reasonable doubt in US history; his defense team, including Scheck and Neufeld, have achieved notoriety in the years since.

Misidentification by Eyewitnesses

Since the original study in the early 1990s on the tendency for eyewitnesses to misidentify perpetrators of crimes, many more studies have been released that continue to corroborate those facts. Eyewitnesses have become notoriously unreliable. They often remember small details but not the big picture, and they are beginning to be treated as less valuable than hard forensic evidence in court cases. This is a big win for the Innocence Project, which has been trying to reform laws in each US state since its inception.

There are two ways that the Innocence Project is trying to reform laws to help prevent wrongful convictions. First, it is trying to make sure that DNA testing is accessible to all sectors of law enforcement, no matter how remote or small. This will help take the burden off of eyewitness testimony in trials. Second, by compensating the wrongfully convicted after they are freed, the justice system pays for its mistake. This should make law enforcement and the court system more interested in convicting the guilty party and should prevent more wrongful convictions in the future.

Looking to the Past

Criminal Justice Degrees Guide compiled a list of ten infamous wrongful executions that could have been prevented by the Innocence Project. The list includes Claude Jones, who was executed for killing a liquor store owner based on the testimony of his friends and a hair found at the scene. The hair was later proven to have been the owner’s—not Jones’—by DNA evidence after Jones had already been executed. Another sad example is the case of Cameron Todd Willingham, who was executed in 2004 for killing his three young daughters in a house fire. Arson investigators testified that the fire was intentional, even though Willingham appealed for years. Five years after Willingham was executed, it was determined that the arson investigators used flawed science in their investigation; this could mean that Willingham may be the first officially declared wrongful execution in the state of Texas. These are just two of many sad cases of wrongful executions, which was part of the drive to form the Innocence Project in the first place.

What Methods are Used to Exonerate Prisoners?

In most cases, prisoners are exonerated based on DNA evidence. The majority of the cases that are taken on by the Innocence Project had convictions that occurred before DNA was regularly tested. Therefore, the lawyers affiliated with the Innocence Project generally move to have evidence looked at again so that anything available can be tested for DNA that may have been overlooked originally. An interesting and important point to remember is that, as long as it is not contaminated, DNA evidence can be preserved for decades. This is especially true with blood and other bodily secretions and hair follicles.

Other forensic evidence may be used to exonerate prisoners as well. In one case, blood type should have proved that the convicted person couldn’t have done it from the beginning; he was eventually exonerated on that evidence. In other cases, the real perpetrator was caught and confessed, exonerating the falsely imprisoned. In one final example, a judge found that a prosecutor willingly withheld evidence of innocence and overturned a prior conviction.

Success Stories

So far, there have been 337 post-conviction DNA exonerations in the United States, along with seven cases where falsely convicted prisoners were exonerated by other means. In many of the cases, the convicted person spent more than a decade behind bars before DNA evidence or other evidence was able to exonerate him. Some even spent time on death row.

Oddee tallied ten of the worst wrongful conviction cases, and it’s easy to see how lawyers can become very passionate about the Innocence Project. William Dillon, for instance, served 27 years for murder, but was released when DNA evidence proved he wasn’t the killer. Kirk Bloodsworth spent nine years in prison—two of those on death row—before DNA testing excluded him. Robert Dewey was freed from a life without parole sentence because of a blood stain on his shirt that supposedly linked him to a murder; 17 years later, that blood was tested for DNA and it was concluded that it was not the victim’s blood. These are only three examples, but they show how the story usually goes when the Innocence Project is successful.

How Does the Innocence Project Work?

The Innocence Project works in a fairly set pattern each time it gets involved in a post-conviction case. Often, the convicted person or the person’s family reaches out to the Innocence Project members, asking them to take a look at the person’s case; other times, the Innocence Project independently hears of a case and offers to take it on. Once the Innocence Project takes on a case, its lawyers work tirelessly to get the evidence reviewed again and to get the case back in front of a judge for reassessment. This process is rarely quick—more often than not, it takes years for the Innocence Project to prevail in a case. There are two end goals that the Innocence Project is always working toward: freeing the wrongly convicted person, and reforming laws that prevent justice in each state where they work.

In concurrence with its work to free the wrongfully convicted, the Innocence Project also continually works toward reforming the justice system in order to prevent future wrongful convictions. This includes strategic litigation, where lawyers on the Innocence Project team work through the legal system to bring attention to the causes of wrongful conviction. Once the causes are made known, the Strategic Litigation team usually works with the Innocence Project’s Policy department to start petitioning to change laws in order to prevent future injustice in the court system.

The Innocence Project in the News

So, why have you been hearing of the Innocence Project in pop culture recently? There are two likely reasons: “Serial,” the ultra-popular podcast from NPR, and “Making a Murderer,” Netflix’s sensational documentary that was released in December 2015.

In the last episode of the first season of “Serial,” Sarah Koenig talks to Deirdre Enright, who leads the Innocence Project clinic at the University of Virginia Law School. Enright said that her students have opened an investigation into Adnan Syed’s conviction, and they have identified another potential suspect. This is entirely separate of the appeals process that Syed is currently going through in the state of Maryland, but will definitely help his case should he get a new trial.

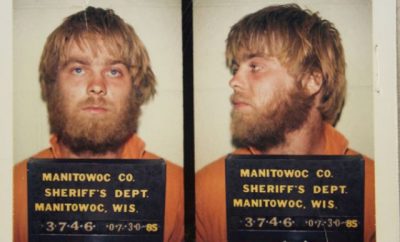

The Innocence Project has been even more prominently featured in the news in the case of Steven Avery, the man who is the subject of “Making a Murderer.” Avery is actually featured on the Innocence Project’s website, because he is a success story for them—he was exonerated after being convicted of the attack and rape of a jogger in 1985. He spent 18 years in prison for that crime before DNA evidence freed him—and two years later, he was back in court, this time facing murder charges in the death of Teresa Halbach, a photographer who was last seen on Avery’s property. He and his nephew have been in prison for that crime for the last 9 years, and the Innocence Project is again involved in Avery’s case.

The Medill Justice Project at Northwestern University–formerly the Medill Innocence Project–has also been in the news in the last year, but for a completely different reason. In February 2015, a man was freed from prison after serving 15 years for a crime he did not commit–but he alleges that he was put in prison after a coerced confession to one of the professors who led the Medill Innocence Project. When he was imprisoned, another man was freed, and it is postulated that the original man was the actually perpetrator. This was very unfortunate press for the Innocence Project, but the program has since been under reform. The Medill Justice Project is now being led by a former investigative reporter for the Washington Post, and has continued to do good work despite the lawsuit.

Conclusion

In the two-plus decades that the Innocence Project has been working toward freeing the wrongfully convicted, it has grown and had many success stories. What started as a small law school clinic in New York, is now a nationwide non-profit with 344 success stories. Forensic evidence has become standard in court cases now, but there are still many prisoners who were convicted based on more circumstantial evidence, like eyewitness testimony. Humans make mistakes, and that has become apparent as the Innocence Project continues to free wrongfully convicted criminals throughout the country. The greater goal now, after two decades of working on individual cases, is to reform laws in each state that allow eyewitness testimony to put away people for crimes in the first place.

Resources

Primary

US Department of Justice: Eyewitness Evidence: A Guide for Law Enforcement

State of Washington: Eyewitness Identification Procedures: Legal and Practical Aspects

The Justice Project: Eyewitness Identification: A Policy Review

Additional

The Atlantic: Making a Murderer: An American Horror Story

Oddee: 10 of the Worst Wrongful Imprisonment Cases

Criminal Justice Degrees Guide: 10 Infamous Cases of Wrongful Execution

Time: The Innocence Project Tells Serial Fans What Might Happen Next

Huffington Post: 7 Terrifying Things ‘Making a Murderer’ Illustrates About American Justice

The Washington Post: Where Do the Cases at the Center of Netflix’s ‘Making a Murderer’ Stand Now?

Columbia Journalism Review: How the Medill Justice Project has Thrived Following Controversy

The Daily Beast: The Innocence Project May Have Framed a Man for a Crime He Didn’t Commit

Comments