Image courtesy of [Greg Matthews via Flickr]

Image courtesy of [Greg Matthews via Flickr]

Law

Drunk Driving on Trial at the Supreme Court

Drunk driving has left parents childless, spouses widowed, and siblings as only children. In 2013 alone, 10,076 people were killed in drunk driving crashes. It has claimed the lives of thousands of people over the years and sparked lobbyist action, which has forced stricter regulation of drunk driving on both the federal and state levels. Most recently, the Supreme Court has agreed to hear a group of three cases, a sequel per se to its 2013 drunk driving decision, in an effort to review warrantless drunk driving tests as a violation of Fourth Amendment rights and the criminalization of a refusal to take a drunk driving test. Read on to learn more about the development of drunk driving as a crime and what the new cases hold for the future.

History of Regulating Alcohol Consumption

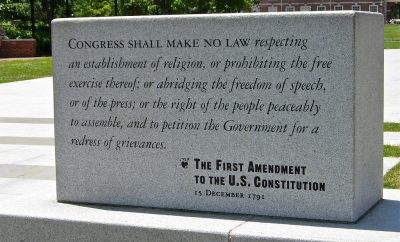

Despite its widely accepted consumption, alcohol is still a drug and one that not only endangers the drinker, but in some cases the lives of others. The federal government and state governments have long been involved with the regulation of alcohol. Mothers Against Drunk Drivers, or MADD, incorporated in September 1980, has been a forefront lobbyist in terms of pressuring the government for stricter and more consequential laws for drunk drivers. Following MADD’s influence, the federal government signed into law the Federal Uniform Drinking Age Act of 1984, which established a uniform drinking age of 21 in the United States and governed state implementation of the Act through apportionment of funding for highway construction, repair, and maintenance. While states have flexibility and control over alcohol policy development and enforcement, the federal government maintains regulation over whether alcohol is sold in the state, whether it can be imported into the state, its distribution, and its possession.

Furthermore, states control the laws pertaining to drunk drivers and the potential consequences and punishment suffered by those charged with drinking and driving. In a breaking development on Friday, December 11, the Supreme Court agreed to review three cases all dealing with the same ultimate issue–“whether a blood or breath test for drunk driving can be made without a search warrant and whether, if there is no warrant, an individual can be charged with a crime for refusing to take such a test.” The upcoming Supreme Court decision will have a nationwide effect regarding drunk driving roadside manner as 13 states make it a crime to refuse to take a drunk driving test. The three cases chosen for review were picked out of 13 submitted because they involved 3 different scenarios regarding drunk testing and hail from both North Dakota and Minnesota.

The Important Legalities of Drunk Driving

While the evolution of drunk driving policy and law-making has a rich history on both a state and federal level, we will focus on post-2000 development. One of the most noteworthy nationwide implementations was finalized in 2004 with the adoption, by all 50 states, of the .08 blood alcohol concentration (BAC) standard and implementation of the per se laws. Such laws establish that if an individual is tested and their BAC is .08 or over, no additional evidence of intoxication is required–that individual is considered intoxicated by law.

![Image Courtesy Of [KOMUnews via Flickr]](http://lawstreetmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/8684229367_7d8104dd42_o-320x195.jpg)

Image courtesy of [Ashleigh Jackson/KOMUnews via Flickr]

However, in 2013, the Supreme Court reviewed Missouri v. McNeely which found that in a routine drunk driving investigation where no additional factors existed which created a special circumstance, exception, or emergency situation, save for the natural dissipation of alcohol within one’s body, a non-consensual and warrantless forced blood test violated the Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable searches of one’s person. The facts of McNeely were straightforward–Tyler McNeely was stopped shortly after 2AM, had admitted to having a few beers, failed a field sobriety test, smelled of alcohol, declined to take a breathalyzer test, and was placed under arrest. The officer did not secure a search warrant prior to taking McNeely to the local hospital where he asked for signed consent for a blood test, which McNeely denied. A lab technician, under the direction of the officer, was told to collect a blood sample from McNeely despite not obtaining consent to do so. McNeely’s BAC was 0.154, almost double the legal limit, and he was subsequently charged with driving while intoxicated.

The Court in McNeely recognized that Fourth Amendment precedent allows for warrantless searches of a person only if the search falls within a recognized exception. A number of exceptions give rise to an exigent circumstance including an emergent need to provide assistance to someone in a home, chasing and pursuing a fleeing suspect, to enter a burning building or investigate a fire, or to prevent the destruction of evidence, among other factors. While the time restraint on testing a blood alcohol level could present an exigent circumstance not only because of the natural dissipation of alcohol, but also for the time required to obtain a warrant, the Court had to analyze the full picture regarding McNeely’s specific situation. They ultimately decided that the State’s argument–that the natural dissipation of alcohol from a driver’s body is considered an exigent circumstance in every case–was unsupported and unfounded on a Fourth Amendment basis. Essentially, the fact that the test may not be accurate hours later after the alcohol wore off was not a good enough reason to perform a warrantless test.

The Statistics of Drunk Driving

Despite the legal disputes around drunk driving policies, statistics have come to show a significant decline in the number of drunk driving deaths from 1982 to 2014. The rate of drunk driving is highest among individuals between the ages of 21-25 with drunk driving costs reaching an upward of $199 billion a year. Furthermore, over 1.2 million people were arrested in 2011 for driving drunk and approximately one-third of those arrested or convicted of drunk driving were repeat offenders. Needless to say, there is work to be done to further drop those statistical reports.

The Supreme Court’s Upcoming Drunk Driving Review

Despite the ruling in Missouri v. McNeely, the Supreme Court is tackling the warrantless blood or breathalyzer test again in addition to assessing the constitutionality of criminalizing the refusal of a driver to submit or consent to a test. Of the three cases taken up for review, two come from North Dakota where it is a crime to refuse a blood, breath, or urine test, one punishable to the same extent as a conviction for drunk driving. The lead appeal comes from Danny Birchfield, who in 2013, drove his car off the road, failed a breathalyzer test, and subsequently refused to take a blood test. Birchfield pled guilty to a misdemeanor charge, but reserved his right to appeal.

The third case operates under Minnesota law, which makes it a crime to refuse an officer’s request to take a blood test, if a valid arrest has been made for drunk driving. William Bernard Jr. was arrested and charged with two felony counts of refusing to submit to a sobriety field test, blood, or breath test. Witnesses reported Mr. Bernard after his truck was struck trying to pull a boat out of the water. Police requested he submit to a test because he smelled strongly of alcohol and was driving the truck–he denied the test and was arrested under Minnesota’s “implied consent law,” agreed to when a driver obtains his or her drivers license and criminalizes a refusal to take a test. Ultimately, Bernard was convicted–a conviction that is in conflict with Missouri v. McNeely because it allowed for warrantless drunk testing and an arrest without the presence of additional factors or emergent circumstances.

![Image Courtesy Of [grendelkhan via Flickr]](http://lawstreetmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/109047024_5667882f64_o-320x240.jpg)

Image Courtesy Of [grendelkhan via Flickr]

Conclusion

The Supreme Court review of the upcoming cases is expected to clarify the issues that McNeely did not, such a bright line rule pertaining to warrantless demands for drunk testing and exigent circumstances, as well as addressing the criminalization of refusal through implied consent laws. Although the Supreme Court may be wary of completely controlling process and punishment of drunk driving, a long-term power of the states, it will have to develop a more clear requirement since the number of cases challenging drunk driving test procedures under Fourth Amendment claims continues to grow, particularly in the 13 states with implied consent laws. Many state rulings allowing for warrantless testing are in direct conflict with McNeely–it is therefore imperative, for continuity and consistency, that the Court create a bright line rule for drunk driving test procedures. Whether it will or not in the upcoming case review is to be determined.

Resources

Primary

98th Congress: Federal Uniform Drinking Age Act of 1984

Additional

SCOTUSblog: Court to Rule on Drunk-Driving Tests

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Alcohol Policy

Foundation for Advancing Alcohol Responsibility: .08 BAC Legal Limit

Mothers Against Drunk Drivers: Drunk Driving Deaths 1982-2014

Mothers Against Drunk Drivers: Drunk Driving Statistics

Bring Me the News: No Warrant Needed: Ruling OKs Arrest if You Refuse Drunk Driving Test

The Chicago Tribune: Supreme Court to Review Blood-Test Requirement for DWI Cases

Comments